Tape Emulation

As audio engineers we live in a very exciting time. The capabilities and quality of the digital audio domain continue to expand and improve at unprecedented rates. High quality recordings are more affordable than ever to make. The commercial studio business is on the downfall, while home/project/mobile studio professionals and hobbyist are on the rise. Many audio professionals perceive this as a negative shift due to a flood of amateur quality audio content released across many social media and music distribution platforms. On the contrary, many see it as an opportunity by embracing the competition and starting their own business from the ground up, on a computer alone. These general trends in the audio business have been underway for quite some time now, but as of the last few years the digital audio tech companies have been releasing products that even veteran and old school engineers alike can be excited about. That is, digital emulation of classic analog masterpieces. Tape machines, compressors, EQs, preamps, and many other popular analog tools that were used to make your favorite records are now being released as plugins to be used within the DAW of your choice. The software is modeled to sound like and be controlled in the same manner as their original analog predecessors. In this article, we will be discussing the digital emulation of tape machines in particular. We will discuss a brief history of analog tape, characteristics of analog tape, common parameters of tape, and last, but not least, plugins that can get you started in no time(well, maybe some time)!

A Brief History

Analog tape machines revolutionized the recording industry in the 1940’s. Not only did they provide superior functionality as a recording medium, but the sound quality was unparalleled for decades. About 20 years later, digital audio technology as a recording medium was in its infancy. It wasn’t until the 1970’s that the first commercially distributed digital recordings were published; however, still decades after the introduction of digital capability, analog tape machines were the preferred medium of recording audio. At some point as we approached the millennium, there was a digital tipping point. The speed, convenience, upward mobility, and ultimately the affordability of digital audio workstations became more practical and efficient than using analog tape to capture and playback sound.

Digital audio workstations as a recording medium now dominate the recording industry. Some can argue that recording to an analog tape machine still sounds “better” than recording in the digital domain with all of its advancements. However, there is no argument against accurate digital to analog conversion, seamless audio editing, one-touch memory locations, and now offline rendering being extremely useful tools that are virtually impossible in the analog domain. The truth of the matter is that many notable audio professionals still use tape machines. Although, instead of using tape as their primary medium of recording, tape is now commonly used in conjunction with a digital audio workstation serving as the main recording and playback device. In this circumstance the tape machine is now used as a unique aesthetic instead of as a recording necessity. In modern professional practice, audio is often recorded into the DAW and then routed to the tape machine at a later time during the mix or mastering process.

Tape Character

Analog tape is, practically speaking, outdated as a means to record sound. However, it (and the emulation of it) is still commonly used to add a character during the mix and master processes. At a basic root of this complex character is a change in frequency response, subtle compression, and saturation of 3rd order harmonics.

In regard to frequency response, we generally think of analog tape as sounding dark and warm. That is, a tape machine gently rolls off high end frequencies and creates a small boost in the lows (called head bump). However, it does so in a way that cannot be achieved with a traditional EQ. That is because an EQ is generally static, meaning it holds its position and does not move. On the other hand, the frequency shifts caused by analog tape are far from static. The tape has a non-linear response, meaning it reacts differently over time based on the dynamics of the elements that are drive the tape. For example, if the drums and bass drop out of a song that is on a tape reel, then the remaining elements will not drive the tape input as hard causing a shift in frequency response; when the drum and bass tracks return to the arrangement the frequency content will shift back to where it was given that the drum and bass player are playing at the same volume as they were prior to the drop out. Essentially, the tape is non linear because its character is dependent on the strength of its input source.

Compression/Saturation

In addition to frequency shifts, analog tape introduces subtle dynamic compression to signals. In other words, if we take a signal that was recorded digitally and run it through an analog tape machine (or emulation of it) the transients of the audio waveform will be smoothed out and appear as less sharp than they were prior to tape. The harder we push the input signal into the tapes ceiling, the more prominent the compression becomes. Once a signal is pushed past the dynamic ceiling of the analog tape, the tape saturation point is reached. Saturation is the point of analog clipping/distortion. However, unlike digital clipping, this distortion is unique, pleasant, and often sought after.

Tape saturation results in the boost of 3rd order harmonics. If you take the fundamental frequency of a source signal and multiply it by 3, then that is where the 3rd order harmonics live on that particular source. Analog gear that is built using tubes tend to generate 2nd order harmonics (Fundamental times 2). More complex source signals saturating a tape machine will generate more complex third order harmonics. These can add a certain brightening and character in a musical way that is non-linear, non-static, and impossible to achieve with an EQ or alone. It is also important to note that tape will distort at lower levels for higher frequency content.

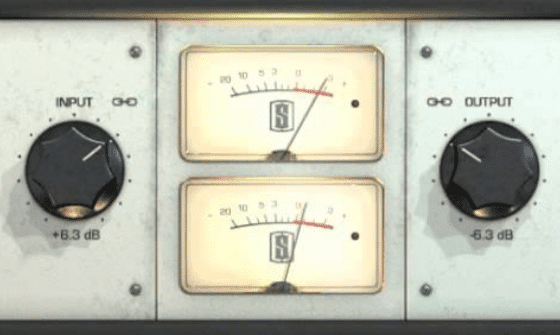

"The popular Slate VTM tape plugin is reaching the saturation point the necessary input gain structure."

Imperfection and Nostalgia

Aside form frequency response, compression, and saturation, the sound and character of analog tape is achieves an irreplaceable character because of its elements of imperfection and nostalgia. Analog tape is an imperfect medium in many ways, but in general it is imperfect because it never plays back the same recording the very same way twice. We will discuss further in depth some of these imperfections and irregularities later on in the article, but overall tape machines are subject to amplitude, pitch, and harmonic phase irregularities.

Wow and flutter, also known as “warble” are varying fluctuations of amplitude and pitch caused by vibration and movement within the physical tape machine. “Wow” is characterized by lower frequency fluctuations and flutter is high frequency fluctuations (Wow < 4Hz…Flutter > 4Hz) Generally, older tape machines are more subject to tape warble in comparison to the modern tape machine. Tape machine emulation plugins actually have controls that allow you to dial in how much wow, flutter, and noise might be desired for any given style. If you are seeking a more retro style or feel you may want to dial in the wow, flutter, and noise parameters to mimc the sound of an older tape machine. Aside from tape warble, we have head bump characterized by a frequency boost in the low end of the spectrum. We will go into more detail about head bump later in the article when we discuss tape speeds, but it is also a harmonic imperfection.

Nostalgia is another essential reason why the sounds of analog tape machines (AND the emulation of them) achieve irreplaceable character. That is, our ears become accustomed to sounds and styles that are familiar. Hit recordings from the mid 1900s that were recorded to analog tap not only established commercial success, but they have stood the test of time and repetition! Thus, the imperfect character of analog tape naturally pleases our ears because it has been commercially fed to us for the majority several decades repeatedly. Acknowledging this is important to do as an engineer because whether analog tape sounds better than digital recording (as a medium) is subjective. Whether analog tape sounds more commercially familiar to the music consumer than digital is not!

Monitoring

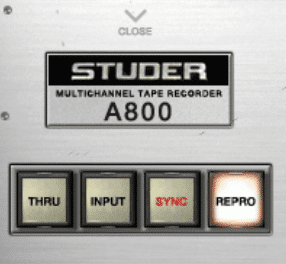

Analog tape machines and emulation plugins have several different settings for monitoring what is in the signal path of the machine. The “Thru” setting will bypass the tape and monitor the source signal as it was originated. The “Input” setting will monitor the signal before it reaches the tape but after it has traveled through the particular machines circuitry. The “Sync” option will allow you to listen to what is recorded on the first reel, but before it reaches the playback reel. The “Sync” head can be easily thought of as the record head, and the “Repro” (reproduction) head can easily be thought of as the playback head. The “Repro” head on a tape machine is optimized for listening back at its highest fidelity. Monitoring from the “Repro” head will give us the full tape experience and coloration. In analog recording, it is also important to note that there is often a time delay between the “Sync” and “Repro” heads, so when overdubbing over existing signals on the record head, be aware of that the performance and playback may be out of synchronization. However, that isn’t a concern in the digital domain.

"Check out the monitor settings on the Studer A800 by plugin by UAD"

Tape Reel Size

In the digital world, we use the DAW to mix down dozens and sometimes hundreds of tracks in the form files. At the end of the mix we typically aim to export all of those tracks down to a singular two channel stereo file. In the analog tape world, it is very much the same concept. However, the tracks are not files as they are physically embedded into the tape upon recording, The track count of tape machines are typically limited to 8, 16, or 2. Also, we have different size tape reels for the multi-track than we do for the 2-track (stereo) reel.

In general, larger track counts require larger analog tape size. A two-inch tape size is typically used for 16 and 24 track tape decks, while smaller track counts would often use a one inch tape size. Once multi tracks are recorded onto one or two inch tape, they are then mixed, typically through a console, and sent to the two-track tape machine. The stereo two-track machine most often uses a half-inch tape size, and some two-track (master) tape machines use a quarter inch tape size.

Analog Tape Type

Analog tape reels come in several types and sizes, and there are notable differences between what they are typically used for and how that affects the resulting sound character/quality. For simplicity’s sake, lets first categorize them on the general scale of old to new. Older tape types reach saturation at a lower level than newer tape reels. That means they have a lesser dynamic range and a higher noise floor. Since older tape types distort easier and earlier, they naturally have the most colored frequency response, which is heavily characterized by a high frequency roll-off. As we move on to newer tape reels, the dynamic range increases, the noise floor is lower, and the result is a superior signal to noise ratio. Since the distortion point gradually gets higher with new tape types, the frequency response becomes flatter and high-end frequency content is restored. Also, the transients become sharper resulting in a fuller resolution, higher definition, and overall punchier sound.

Now, let’s replace the general old to new scale with actual names and calibration levels. In short, a calibration level implies a suggested sweet spot for the levels of audio going onto the tape. Here are the tape types from earliest to latest and their suggested calibration levels:

- 250 type = +3dB suggested calibration

- 456 type = +6dB suggested calibration

- 900 type = +9dB suggested calibration

- GP9 type = +9dB suggested calibration

Keep in mind that the tape deck (not the tape itself) is calibrated to operate at a certain signal level. The tape type suggests a recommended calibration level, but it is not a requirement to calibrate the tape deck at that level. It is merely a suggestion.

Tape Speed and Head BumpAnalog Tape Machine Speed and Size

Although the tape type affects frequency response of the audio, the speed of the tape machine has the greatest effect on its frequency content. The most common speeds of analog tape recorders are 7.5, 15, and 30 (ips). The speed of a tape machine is measured in inches per second or “ips” and it has the most effect on high and low frequencies. As we have stated previously in the article, the sound of analog tape is generally characterized by the roll off of high frequencies and a boost in the low frequency band. Tape machine speed highlights these characteristics. Slower tape speeds result in greater attenuation (reduction) of high frequencies and more aggressive boost of the lows. We call this boost of the lows “head bump”. As we increase speed the high cut and low boost is less exaggerated and the head bump frequency moves to up into slightly higher band of the spectrum. In addition, fasster tape speeds are considered higher in fidelity because of their flatter frequency response across the spectrum. Faster speeds also subtly reduce the effects of wow and flutter and even noise in comparison to slower speeds. Since the noise is also reduced, higher tape speeds imply a better signal to noise ratio and increased dynamic range. Since faster speeds provide many technical benefits in regards to fidelity, accuracy, and noise, 30 ips is often a go–to setting for mastering and mix bus applications.

Bias

Bias is a common parameter you will find on analog tape machines and tape emulators. What it does is add a signal that is above the audible frequency spectrum during playback. Humans tend to be able to hear approximately from 20Hz to 20 kHz, and bias signals are over 40kHz and often up to around 100kHz. The general purpose of bias is to increase the audible signal quality by evening out the frequency responses and volume linearit. It also helps reduce distortion. The concepts that make bias work well for tape recording are not easily understood, but the applications of it are very straightforward. Since bias is used to reduce overall distortion levels, a low bias setting will result in more distortion and higher bias setting will result in less overall. The difference in distortion levels will be particularly prominent and noticeable within the low end of the frequency spectrum. A high bias is also known to take off high frequency edge like guitar pick striking harshness. Play with the bias parameter! The differences will be subtle, but have the ability to really bring out the character of bass oriented instruments especially.

Flux

Flux is another useful parameter on tape machines and emulators that can more precisely dial in desired distortion and noise levels. Flux is also known as the operating level, and it controls the amount of magnetic force that is coming off of the record head. Lower flux setting will allow the input signal to reach distortion earlier, while higher flux settings allow for more headroom before reaching distortion. Thus, higher flux settings imply the ability to achieve larger dynamic range with lower relative noise levels in comparison to the input signal.

Digital Emulation Plugins

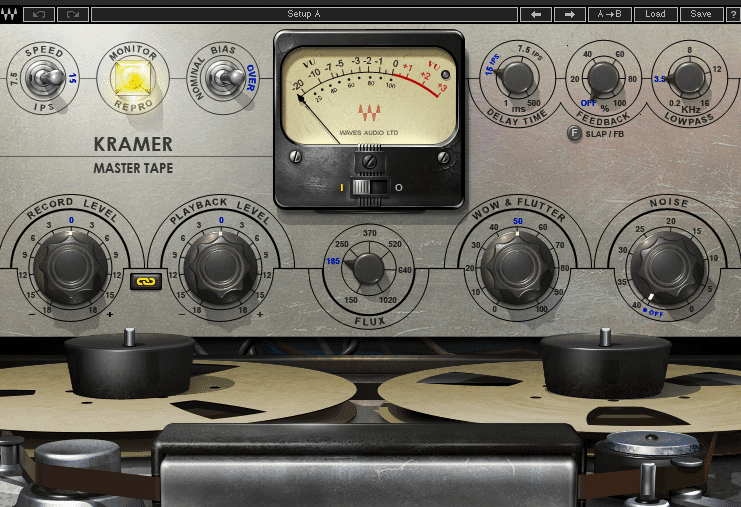

There is a plethora of digital tape emulation plugin options available for those without the funds space, or time for a real tape deck. Waves, UAD, and Slate (plugin manufacturers) all make reputable tape emulation plugins. Try them out if demos are available, and pick one for your needs based on the information above. Although, do not be afraid to experiment with any tape emulator. For example, Waves Kramer Tape plugin is modeled after a vintage quarter inch tube tape machine. The type of tape machine it is modeled after is meant for mix bus, sub group, and mastering applications, but it can achieve great results on singlular tracks of all kinds. In particular, try driving your bass or kick to the point of distortion, or try a subtle tape effect on vocal tracks. Instead of reaching for a distortion plugin, reach for the tape machine and crush it hard and use the tape as the distortion. The options are endless, but be sure to familiarize your self with how the VU meter functions and adjust your input gain accordingly to align with intentional sonic goals.

Be creative. The digital domain gives us freedom to stack multiple instances of a variety tape machines, reorder them, or use dramatic settings without anything to lose! If it isn’t a positive change or parallel addition (with appropriate gain a/b matching of course) then just hit undo. Don’t be afraid to use the tape for its effects, as well. Digital tape emulators are commonly loaded with effects settings. Analog slapback delays are popular choice for rock and pop vocals, and extreme wow and flutter settings can be used to create help psychedelic masterpieces with string instruments. Again, the options are endless.

Also, keep in mind that many of the parameters that are discussed earlier in the article were traditionally used to calibrate the analog tape machine. Parameters like flux, bias, and even tape speed usually stay put once chosen in the analog realm, but digital allows us to change speed, flux, and bias creatively. Use that to your advantage, and learn the subtle of the magic that is analog (emulation). It is important to note that many analog tape machine plugins have a noise or analog hiss parameter. While the noise can be sought out for certain types of rock and folk music, it is not commonly used in modern music trends. Modern music tends to have a very low noise floor which results in a “clean” sound. Also, if you aren’t aware of the hiss/noise parameter when it is on, it can be quite difficult to pinpoint where or what plugin the noise is coming from if you are aiming to get rid of it.

"The Kramer Tape plugin by Waves has a wide variety of parameters. It is an extremely versatile tape machine plugin."

Final Thoughts

The results of using the sounds of an analog tape machine are complex, hard to describe, and most importantly, natural. The analog tape machine and its functions as a subject has depth, and this article aims to provide the fundamental knowledge to use tape emulation and its various parameters effectively, but it is still just scratching the surface. Embrace the fact that digital emulation is available, because it just may be the missing piece to achieving the classic sound you’ve been seeking. Interestingly, it is often thought that the analog tape is pleasing to the human ear because it is much like the human ear. That is, the sound the human ear perceives is often combined with underlying noises within our body like the cracking of joints, the growls of the stomach, and the sound of our own breathing. This is much like the underlying noise floor of tape, the pop and crackle present in tape recording, and the wow and flutter caused by the physical movement of the machine. The human ear perceives sounds differently environment, temperature, humidity, and movement, as does the analog tape machine. It is a beautiful thing, and no single distortion or EQ plugin can achieve such natural sonic complexities. Do your self a favor, and reach for a tape emulation plugin.