Best Mastering Level for Streaming

Quick Answer

The best mastering level for streaming is an integrated -14 LUFS, as it best fits the loudness normalization settings of the majority of streaming services. Although other measurements like the true peak value and other metrics need to be considered, -14 LUFS is the best mastering level when considering loudness.

Best Mastering Level for Streaming in Detail

Streaming introduced new specifications mastering engineers need to account for when mastering.

Whenever a new medium is introduced in music, be it the compact disc, cassette, vinyl record or what have you, engineers need to put their heads together to figure out the specifics. Sometimes these specifics are easy to understand, but almost always, reaching any conclusion takes some trial and error, along with a deep understanding of the technology in question.

The latter situation is what we had found ourselves in as we speculated the best approach to mastering for streaming. Since streaming’s inception, the best way to master music as it relates to loudness and peaking has been a topic of debate. And to a certain extent, it’s still is a topic of debate.

Although mastering engineers don't really gather to discuss loudness (even though it would be funny if they did), there is still a debate waging regarding loudness normalization.

Fortunately, after a fair amount of research and experimentation by many engineers and audio enthusiasts, it can be said with a fair deal of certainty that the best loudness at which to master your music is -14 LUFS. This means a few different things.

First, it means you don’t need to concern yourself with additional plugins to determine your loudness penalty, or in other words, a plugin that shows you to what extent your music will be turned down.

Although plugins exist to measure loudness penalty, they aren't necessary for understanding how to properly master your music.

Secondly, you can be comfortable mastering your music to one loudness without the fear of truncating your dynamic range, or distorting your master on various streaming services if the right precautions are taken.

When mastering to -14 LUFS, your master can be distributed to multiple streaming services without distortion or dynamic truncation.

And lastly, you can start focusing on other aspects of your master that are just as important, like how peaking, encoding, and loudness normalization relate to how your master is ultimately portrayed when streaming.

More important than normalization is peaking and inter-sample, both from encoding and from D to A conversion.

With that said, let’s look at these points in detail, as we discuss why you only need to master to an integrated -14 LUFS.

But first, if you’d curious how your mix would sound mastered professionally, send it to us here: https://www.sageaudio.com/register.php

We’ll master it for you using solely analog equipment, and send you a free mastered sample of your mix.

Why -14 LUFS?

This is the big question. How did -14 LUFS get chosen as the primary loudness at which to master music for streaming?

Why -14 LUFS, is a fair question to ask.

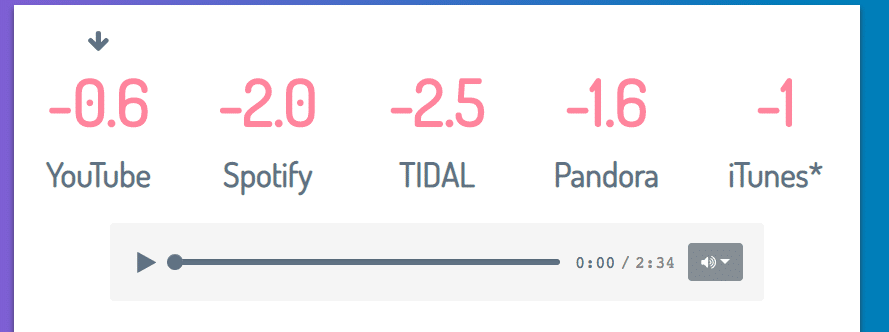

Simply put, it’s the volume to which the most popular streaming service normalizes music. Although Apple Music and YouTube hold a great deal of clout in the music industry, Spotify currently holds the largest subscription base of any audio streaming service, with over 100 million paid subscribers and 217 million users in total. That being said, if someone is streaming music, odds are it’s going to be on Spotify.

The majority of music that is streaming, is streamed on Spotify.

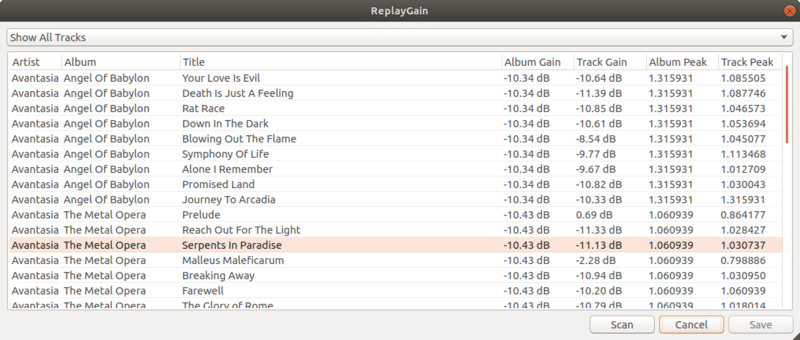

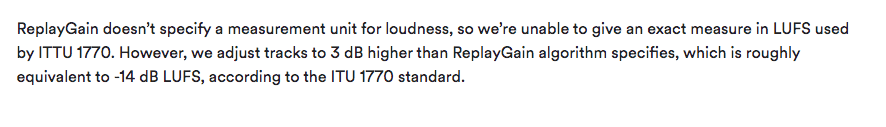

Whenever music gets distributed to Spotify, the audio is stored, cataloged, and then encoded with information with a program known as ReplayGain. This program either turns up or down the volume of the track to the default -14 LUFS, depending on how loud the master is in comparison to that benchmark.

Spotify utilizes ReplayGain for its loudness normalization.

Now it should be noted that although ReplayGain doesn’t alter a master’s loudness to directly correspond with an integrated -14 LUFS, the results are incredibly close. Furthermore, Spotify has stated its plans to conform to the ITU 1770 standard, which uses an integrated LUFS as its measurement system.

Spotify plans to use ITU-1770 metering in the future.

This indicates that regardless of how music is normalized today, anything that has been uploaded to Spotify will eventually be held to the -14 LUFS standard. This gives a more than adequate reason for anyone distributing their music to Spotify, to master to or directly below an integrated -14 LUFS.

How does -14 LUFS Relate to Streaming Services Other than Spotify?

In truth, this information is hard to determine. Although we know that Youtube and Apple Music normalize audio to a similar benchmark as Spotify, they haven’t revealed exactly how they normalize audio.

Some report it to be an integrated -12 LUFS for YouTube and -16 LUFS for Apple Music, but these figures are more or less speculative. In fact, there are reports of YouTube normalizing audio to various volumes, or flat out not normalizing the audio at all. Perhaps it depends on the type of audio, be it dialogue or music, but this can not be said for certain.

What we can say with certainty, is that uploading a master file with an integrated LUFS of -14 will not be harmed by Apple’s or YouTube’s normalization process. This is due to a few reasons.

Even Spotify accounts for various loudness settings.

The first, loudness normalization does not affect the dynamic range of a recording. It only turns your master up or down according to a set benchmark loudness. Having your music turned up by loudness normalization or down by loudness normalization doesn’t change the distance between your master’s quietest and loudest moments - it only changes the relative volume at which all those moments occur.

All this to say, that mastering for Spotify, and then having your music distributed to Apple Music won’t result in a truncated master, only a quieter master.

Loudness normalization doesn't work like a limiter - it doesn't affect dynamic range.

The same goes for YouTube. Having your music turned up by its loudness normalization won’t make your master more dynamic. The only way this process can affect your master is by affecting its amount of clipping distortion - which is a reason for concern but can be avoided with certain precautions.

Remember when I said that mastering your music to -14 LUFS will allow you to focus on other, more important things? Well, these are the important things to which I was referring. Read the next section for the details.

If you’d like to learn more about mastering for other streaming services, you can check out our blog on the topic here: “Master Music for Streaming.”

How True Peak Metering and Encoding are Incredibly Important

Much talk and time has been spent on normalization. In some regards, this concern for loudness can be seen as an extension of the loudness wars, in that loudness is taking precedence over more important things.

Maybe that’s an exaggeration, but the truth of the matter is, all this time we’re spending worrying about how loud our masters should be is time we can spend better understanding the relationship between the encoding process, loudness normalization, and inter-sample peaking.

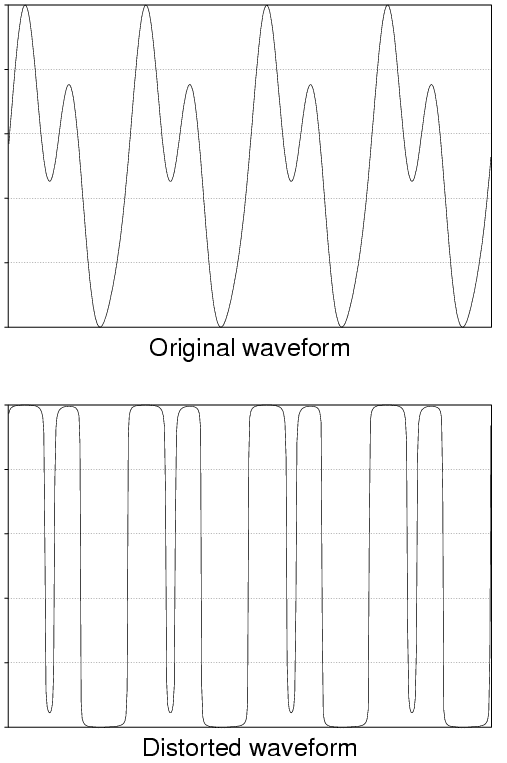

What’s more concerning than an integrated loudness is the potential of unwanted distortion. Unfortunately, this unwanted clipping distortion is something that occurs frequently during the encoding process.

If pushed, masters can clip during the encoding process.

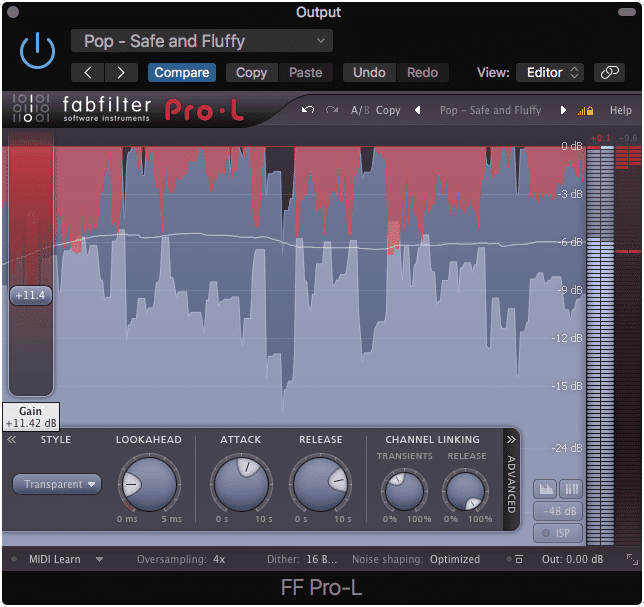

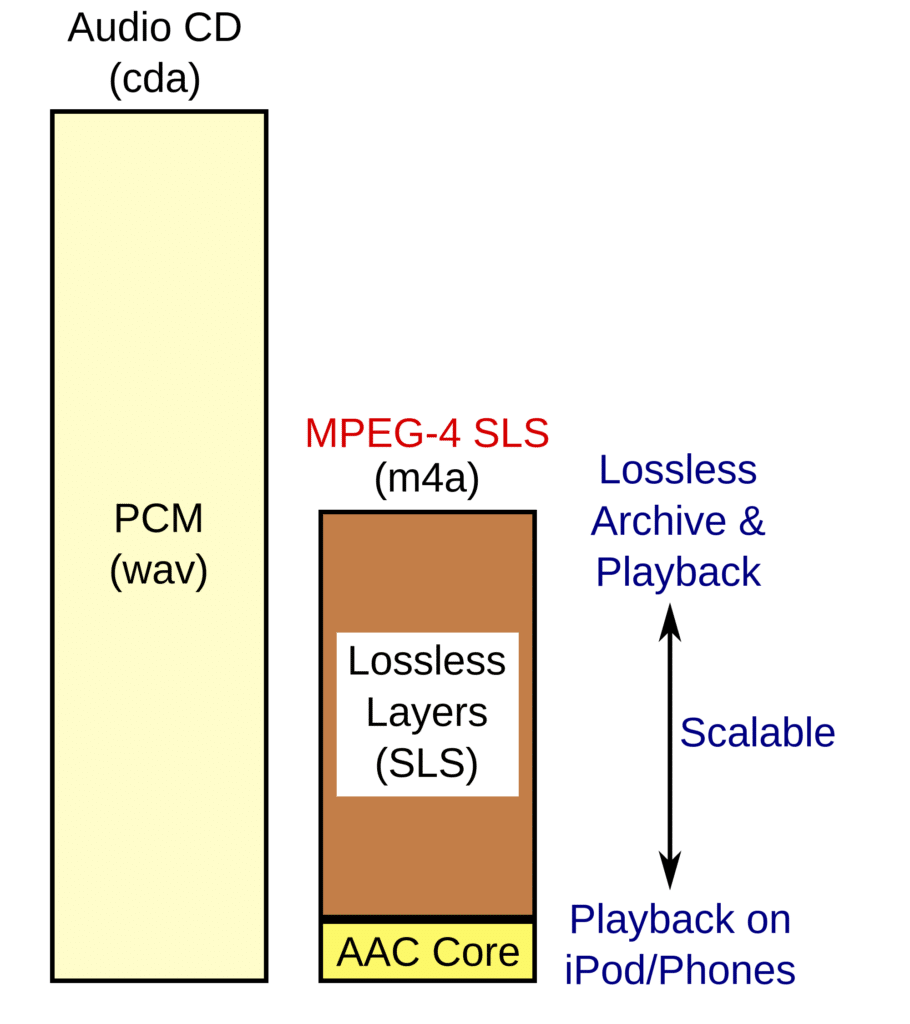

In short, the encoding process can be understood as converting a PCM file like a WAV or AIFF to an MP3 or similar lossy file type. For Spotify, PCMs are converted to Ogg files, and for Apple Music, they are converted to AAC files.

Apple's latest AAC encoding process starts with a PCM file.

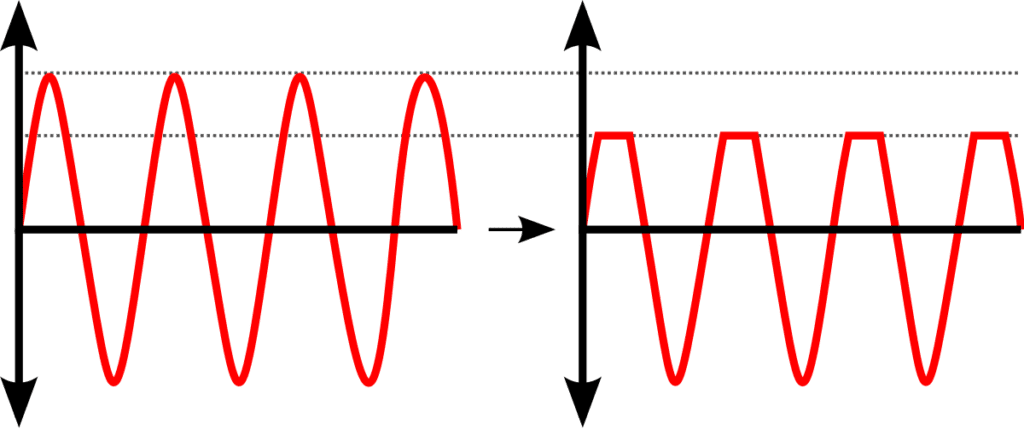

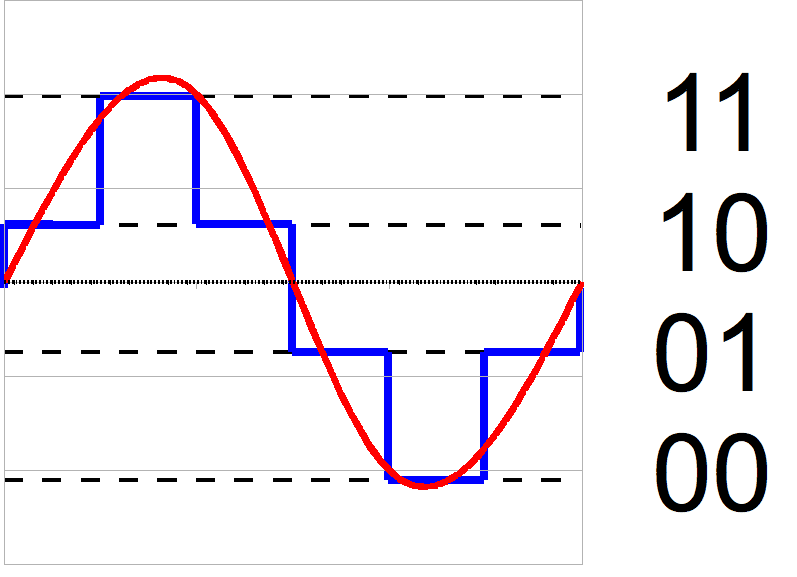

Essentially, during sample rate conversion and bit depth reduction, amplitudes that could otherwise be accurately represented by a bit of data can no longer be accurately represented when that bit is no longer available. This results in both quantization distortion and clipping when converting the signal from a digital to an analog signal.

If the red wave above was limited to only the bits provided by the blue line above, you'd lose a significant amount of your signal.

If you’d like to learn more about this process, here is a blog that goes into greater detail on the subject: “ What is Dithering****?”

The quantization distortion part of this problem is the difference between the original signal and the new signal, as the information that could not be encoded properly is converted into noise, or in extreme situations, harmonic distortion.

Unfortunately, not much can be done to remedy this on the end of the mastering engineer, at least not when the bit-depth is being reduced during encoding; however, precautions and techniques are implemented on the encoding side of things.

When it comes to clipping that’s associated with the encoding process, these can be avoided on the mastering side of things. There are a couple of tools that can be used to see if your music will peak when encoded or when played back.

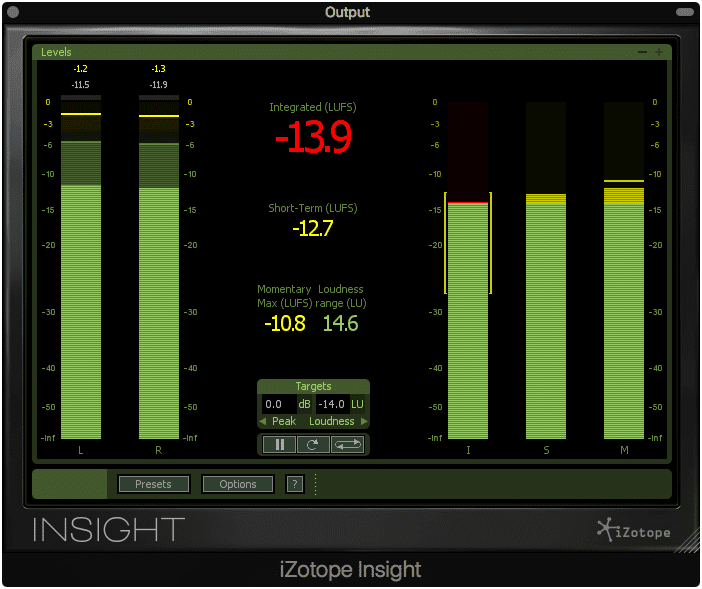

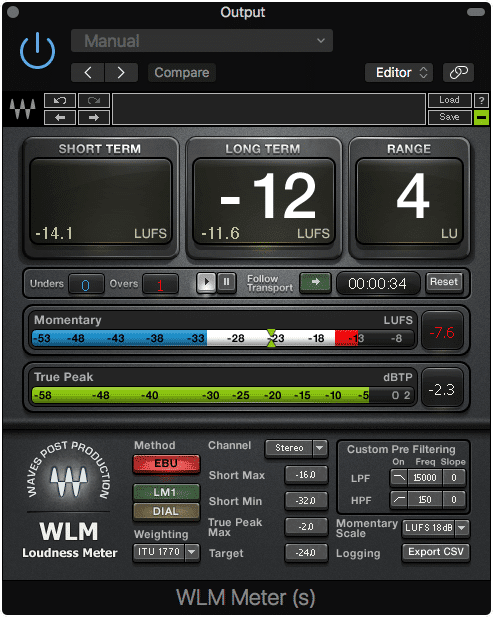

True Peak Meter

A true peak meter accounts for the D to A conversion when music is played.

The first is a true peak meter. This meter measures the inter-sample peaks that can exist when converting a digital signal to an analog signal. It should be noted that although you may not see peaking on your left or right channels, there can still be inter-sample peaks that exist during playback.

As stated a moment ago, the encoding process alters the relationship between a signal’s amplitude and the digital information that can be used to represent this amplitude. When this occurs, inter-sample peaking can become exacerbated as the accuracy of quantization can be diminished.

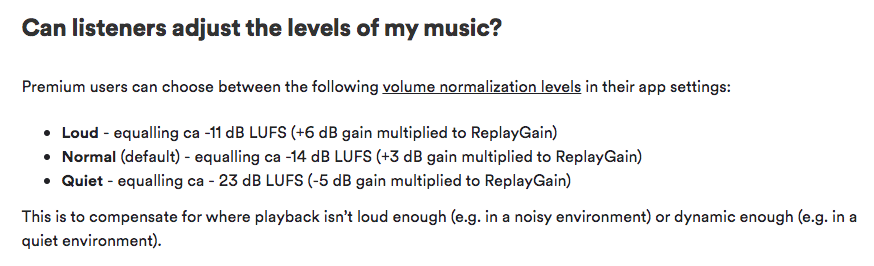

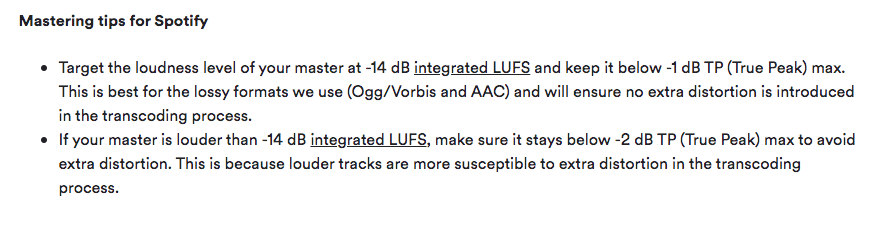

Keeping your master's peak below -2dbTP is a great way to ensure it would distort during encoding.

This makes using a true peak meter even more important. It also means that the loudest peak of your master should not exceed -2dB on a true peak meter. The reason being that the encoding process will alter how amplitudes are quantized, in turn changing the nature of inter-sampling peaking and the D to A conversion process.

Furthermore, loudness normalization will no doubt alter the loudness of your master - meaning that peaks which wouldn’t have distorted during playback can now distort if dynamic enough.

Spotify recommends reducing your loudest peak to ensure clipping doesn't occur.

For example, if a song has a LUFS of -14, with it’s loudest peak at -.2 on a true-peak meter, and it was normalized to -12 LUFS, this -.2 peak could become a problem. Since normalization is pushing the signal louder in this instance, up by roughly 2dB, that peak will become louder as well. Even though the streaming service may account for this with a limiter, an inter-sample may still be created.

Spotify will use a limiter on highly dynamic masters. Be sure to control your dynamics so they don't become truncated by brick wall limiting!

However, if this peak was controlled to -2dB or lower on a true-peak meter, then the extra gain from normalization wouldn’t result in an inter-sample peak. The 2dB of gain added during normalization would push the signal to right below peaking.

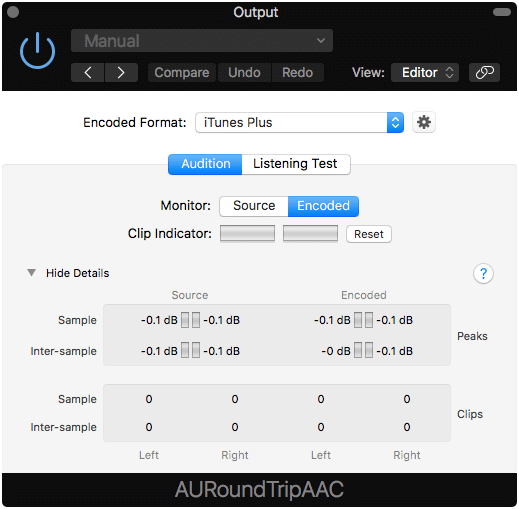

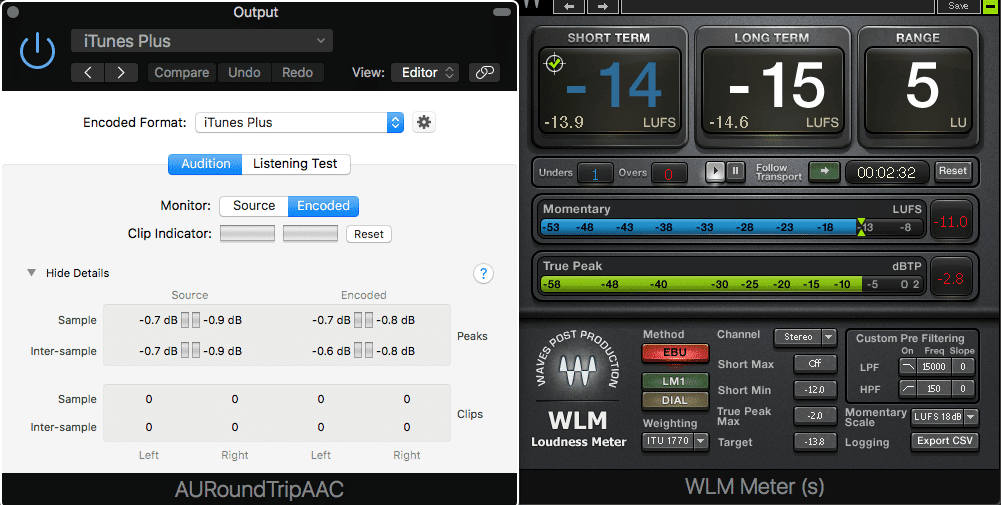

AURoundTripAAC

This plugin shows clipping and inter-sample peaks in real-time.

This second tool is a plugin from Apple, that allows you to see both peaking and inter-sample peaking in real-time. What’s more, this plugin allows you to switch between different encoding processes, to measure if that process results in peaking.

Unfortunately, this plugin only measures the AAC encoding process , and will in turn only demonstrate how your master will be altered for Apple Music. With that said, it still demonstrates how encoding can alter your signal, and gives more reason to monitor your true-peak meter.

Ogg Vorbis Logo - Spotify typically uses the Ogg lossy format for streaming. Not Apple's AAC file.

Keep in mind that when using this plugin, normalization may still affect the overall volume of your track and in turn affect inter-sample peaking during playback. However, utilizing this tool with a true-peak meter can ensure that your music won’t peak during the encoding or playback process.

All this to say, that mastering to a -14 LUFS isn’t the only metric you need to pay attention to. But, by mastering to -14 LUFS, you have a good mid-ground so to speak for multiple streaming services. What’s truly important is how your integrated loudness relates to your dynamic range, as making a highly dynamic master louder through normalization can result in peaking. Understanding how encoding affects your master’s level needs to be paid attention to as well.

The relationship between encoding and inter-sampling peaking is more important than loudness normalization.

Again, it’s not as simple as mastering to -14 LUFS, but -14 LUFS does serve as a good foundation for loudness, from which you can measure both your true peaks and encoding peaks. The relationship between these things - your loudness, your true peak value, and your peaks post encoding is what truly matters when mastering for a streaming service.

So just to recap, when mastering for Streaming

- Master to an integrated LUFS of -14

- Control your loudest peak to -2dB on a true peak meter

- Use the AURoundTripAAC plugin to measure the potential peaks created by encoding

The Loudness Penalty and Plugins that Measure it

The loudness penalty is something we’ve discussed before in great detail.If you’d like to learn more about it here is a blog that covers the topic: “ Loudness Penalty****”

Loudness penalty plugins can show you how much your music will be turned down, but focus attention on the wrong aspect of normalization.

But the reason for bringing it up again is to explain why the notion of a “Loudness Penalty” isn’t too terribly important when considering the other possibilities that come with streaming, loudness normalization, and the encoding process.

Audio distortion from inter-sample peaking deserves a fair amount of attention, as it makes a noticeable change to streamed audio.

The idea behind the loudness penalty is that the worst thing that can occur to your master during the streaming process, is having it turned down by loudness normalization. But, as detailed above, there are worse things to concern yourself with when mastering for a streaming service.

In fact, one could argue that it’s worse to have your master turned up during loudness normalization than turned down. At least when your master is turned down, you don’t have to worry about inter-sample peaking as much as you would if your music was very dynamic and turned up.

All a loudness penalty plugin does is show you to what extent your music will be turned down or up by streaming service, and this may be valuable - but only valuable in how this information relates to the true peak value of your master and it’s eventual encoding process.

This isn’t to say that if you want to purchase one of these plugins you shouldn’t, but just to shift the emphasis or concern from how your master is normalized, to how your master may distort if the transition from your PCM file to a streaming service’s lossy encoding and playback isn’t properly thought out.

Conclusion

-14 LUFS will be sufficient for most streaming services.

Mastering for streaming may be complex, but it's not as complex as it has been portrayed to be. If you are curious at what volume you should master your music, an integrated -14 LUFS is a great place to start and will be adequate for most streaming services. It is also the default loudness normalization setting of the currently most popular streaming service, Spotify.

Instead of spending hours debating the perfect loudness for each streaming service, perhaps it’s wise to consider some other variables that can cause some serious damage to your master. The first being distortion that can occur during the encoding process, and the second being distortion that can occur during the digital to analog conversion.

If you make your master too loud, or your master is normalized too loudly, inter-sample peaks can cause distortion when your music is listened to. This distortion may occur regardless of whether your output meters are showing these peaks or not.

This problem can be exacerbated by the encoding process, which creates inaccuracies in the digital encoding, or quantizing, of a signal’s amplitude. These inaccuracies may result in greater inter-sample and regular sample peaks, in turn causing clipping distortion if severe enough.

There are two tools with which you can remedy these issues and ensure that when mastering, a loudness of -14 LUFS will be sufficient for all streaming services. These tools are a true peak meter, and an AURoundTripAAC plugin to measure the effects of encoding.

If you master your music to a -14 LUFS, and you control your peaks to roughly -2dB on a true-peak meter, you shouldn’t have any issues when your music is distributed to various streaming services.

If you’d like someone to handle this mastering process for you, just to ensure everything is handled correctly, send us one of your mixes here: https://www.sageaudio.com/register.php

We’ll master it for you and send you a free mastered sample in return.

How loud do you master your music?